In an environment where every minute counts, and vital decisions are made in seconds that are in many cases a matter of life and death, the medical staff that make up the Emergency Room Department are a devoted team of people. These doctors, nurses, surgeons, technicians, coordinators, administrators, and supporting staff work in an atmosphere that is as demanding as it is essential. To get a glimpse of this world, read these five different personnel stories from each major ER in the region.

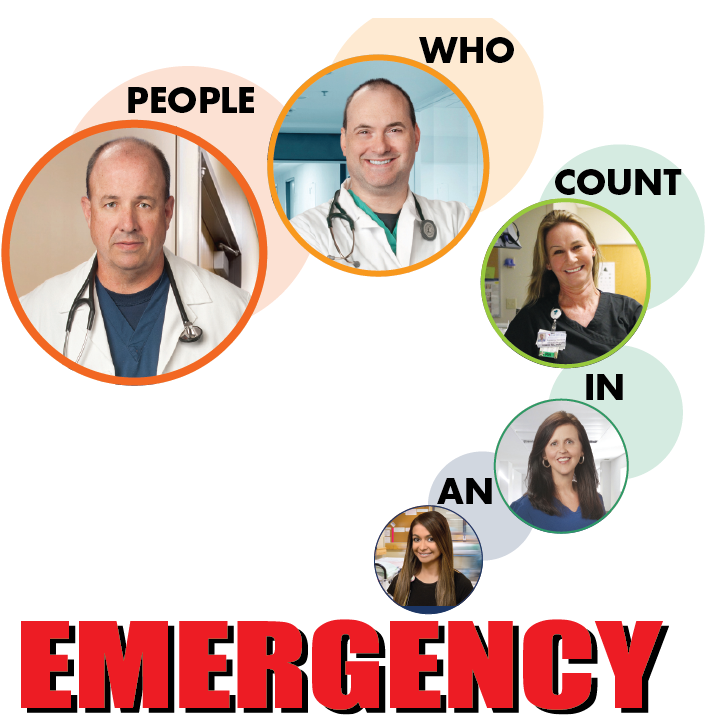

Winter Haven Hospital’s Dr. Ronald Berman

Bartow Regional Medical Center’s Dr. Brian James

Heart of Florida Medical Center’s Clare Merrill, RN

Lake Wales Medical Center’s Theresa Jenkins

Lakeland Regional Medical Center’s Marjan Conklin

Winter Haven Hospital

Ronald Berman, MD

Becoming a jack of all trades to live a childhood dream

Dr. Ronald Berman became interested in becoming a doctor in childhood, when he spent many days and nights receiving emergency care for injuries. “It seemed I always felt better after being treated in the Emergency Department,” the 54-year-old recalls.

When it came time to choose a college major, he wasn’t sure if he wanted to study engineering or medicine. His guidance counselor suggested he study engineering. “His reasoning was a degree in engineering would prepare me for any career that I may choose,” he says. “He told me that if I pursued a pre-med degree, and then decided to go into engineering, I would essentially have to repeat four years of college.”

So he studied engineering, earning a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Philadelphia’s Drexel University and a master’s degree in electrical engineering from the Los Angeles-based University of Southern California.

At age 32, he enrolled in Philadelphia’s Temple University to pursue his medical degree. “After being part of the team that built and tested the night vision system that was used to rescue the medical students from the island of Grenada during the Cuban invasion, as well as helping to build and test a payload on the Milstar Military Communications Satellite, I decided my dream of becoming a physician was possible,” he explains.

Today, Dr. Berman chairs the Department of Emergency Medicine at Winter Haven Hospital. He pulls clinical duty in the Emergency Department, sits on multiple hospital committees, and works with Emergency Room Clinical Director Jenny Blank and hospital administration. “My overall task is to ensure medical professionals in our group provide quality, compassionate care to our patients,” he says.

Like others who work in emergency care, Dr. Berman likes having the opportunity to make a real difference in people’s lives. “Whether we are saving someone’s life, taking the time to counsel patients on the importance of taking their medications, discuss the dangers of smoking, or just treating their pain— I feel we have made a positive impact on someone’s life,” he explains.

Among the most challenging times are those when he must deliver bad news. “Patients don’t fully understand the limits of the field of medicine,” he continues, “and therefore expect us to be able to fully diagnose and treat every complaint that they may have during their stay in the Emergency Department.” Some of the most memorable moments are often the saddest. “I can never forget the infants and children that I have treated who sustained major injuries, drowned or I have diagnosed with life-threatening illnesses,” he says.

But there are bright spots. “One of my favorite and more lighthearted moments in the ER was when I was asked to see a very sick child. After we treated the young patient, I walked back into the room and found the child sitting up in bed with a dispenser of our blood tube adhesive labels,” he recalls. “He was covered from head to toe in the yellow stickers. The picture was priceless.”

As an emergency doctor, he is a jack of all trades. “We treat minor complaints such as aches and pains, cuts, broken bones, and cough and colds, to life-threatening conditions such as heart attacks, strokes, and major trauma,” he says. Emergency doctors also stabilize psychiatric patients and perform life-saving procedures such as intubations for patients who need assistance breathing. “Mostly, we provide comfort to sick patients as well as their families,” he adds.

A Philadelphia native, Dr. Berman did his residency in Emergency Medicine at the Philadelphia-based Medical College of Pennsylvania. He also serves as assistant clinical professor at University of Florida Department of Emergency Medicine and has worked as an emergency physician for 15 years, all of which, have been the most challenging and rewarding of his profession.

Bartow Regional Medical Center

Brian James, MD

Living through the Challenges, Living for the Victories

One of the toughest challenges for Emergency Room physicians is losing a patient. When they do, they’ve got to pull themselves together, put on their bedside manner, and visit the next patient. “You’ve got to be upbeat. You’ve got to clear the slate. You can’t let it rattle you,” says 44-year-old Dr. Brian James, an emergency medicine specialist at Bartow Regional Medical Center.

Brushing against death on a regular basis could make him and Bartow Regional’s ER crew jaded, but there are ways they manage the stress. “I see dead people every two or three days. People go to the ER to die in a lot of cases,” he describes. “We make a lot of morbid jokes in the ER. We either laugh or we cry.” When a baby dies, everyone in the ER may cry. “Sometimes there’s no way to joke around about that,” he adds.

As he stands at what he calls the “curtain of death,” Dr. James recognizes his job is to not to win every time, but to do the best he can with the skills he has. Sometimes that means losing to death, and helping assuage the family’s emotional pain as a consolation prize. “You take what wins you can,” he says.

But Dr. James lives for the good times— when he can come in, fix the problem, and save a life. “There’s nothing like that on the planet,” he explains. “It’s pretty much a blast.” He doesn’t need to search for meaning in his life. “I never worry that I can make a difference,” he says.

The life of an ER physician is demanding and somewhat unpredictable. Dr. James puts in 12-hour shifts, sometimes in the daytime and sometimes at night. He works nights and weekends. “We live and thrive in chaos,” he says. Yet, being an ER doctor only takes second place to his marriage with his wife, Erika. “Actually, I was an ER doctor first. She trumped it,” he says.

A Fort Worth native, he earned his medical degree from University of Texas-Southwestern in Dallas. He did his residency and internship at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, where President John F. Kennedy was taken after his fatal shooting in 1963.

They met while Erika was in Dallas doing her residency in pediatric dentistry. The couple later moved to Florida, where Dr. James earned his Master’s degree in Business Administration from the Gainesville-based University of Florida. He worked for a decade as a medical director, but left administration after Erika was diagnosed with breast cancer. She has been in remission for three years. “We realized we only have one shot,” says Dr. James, who lives in Zephyrhills where his wife practices dentistry. “You can’t keep your own happiness on the back burner.”

For Dr. James, that meant more time with Erika and more time working with patients. What makes him happy is being an ER doctor. He asserts, “I couldn’t imagine doing anything else.”

Heart of Florida Regional Medical Center

Clare Merrill, RN

Finding her love of working with patients and calling in the ER

In a fast-paced Emergency Room, compassion and a “thick skin” go hand in hand. For 50-year-old Clare Merrill, the clinical coordinator at Heart of Florida Regional Medical Center (HOFRMC), they are an important part of her job. “You’re either cut out for it, or you’re not,” Merrill says. “You have to have the compassion . . . or else you’re in the wrong profession.”

Her job is to make sure things run as smoothly as possible in the Emergency Room. That involves overseeing the nurses and doing paperwork. Not everyone can handle the stress caused by a stream of cardiac and respiratory patients. Or whoever arrives at their doorstep. But Merrill has found her niche in the ER. She embraces that stress. “I like the responsibility of knowing I can make somebody better, or help them,” she explains. “You’re always going to find something different from each patient. That’s what I enjoy about this.”

As Merrill puts it, a nurse wears “many hats.” Besides addressing a patient’s physical needs, nurses may need to explain to a patient more fully what their diagnosis is and answer their questions— at a time when they may be scared about what is happening. She believes having that understanding is part of healing. “As a nurse you have to be a strong personality,” she states.

For Merrill, that means staying professional in the tough times, like when a child comes into the ER. Or with some folks they refer to as “frequent flyers” because they return regularly to the ER with chronic illnesses. The nurses bond with them— and with those she calls “walkie talkies”— who come in talking to the staff, only to die a short time later from cardiac arrest. “You do have to develop a thick skin in the ER,” she admits.

Sometimes Merrill helps new nurses through these challenging times by talking with them about it. “It doesn’t happen a lot,” says Merrill, who describes the nurses as “quite competent.”

For eight years, Merrill worked as a house supervisor, overseeing nursing care for the whole hospital. “I always picked up a day in the ER,” says Merrill, whose love is working with patients. “That’s what I went into nursing for . . . to help people feel better. I like the challenge of it, especially down here.”

She also enjoys the teamwork that is part of her job. “We can always rely on one another,” she says.

Originally from England, northeast of London, Merrill has been at HOFRMC for 12 years. Before that, she did agency nursing in the Orlando area. She holds an Associate’s of Science degree from Valencia Community College in Orlando, and plans to begin working towards her Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing online in January. She is unsure if she will pursue a degree as a nurse practitioner, stating, “Right now I enjoy what I’m doing.”

Lake Wales Regional Medical Center

Theresa Jenkins, RN

Her love language is acts of service

Not everyone can thrive in a fast-paced Emergency Room. But, for Theresa Jenkins, a charge nurse at Lake Wales Medical Center (LWMC), the job is exciting. “Every day is different,” says the 44-year-old. “There’s never one day that is the same. You never know what is coming in through the door.”

From gunshot wounds, to heart attacks and strokes, to women about to deliver their babies— even though LWMC doesn’t have a maternity ward— the ER team handles it.

“Every day, before I go to work, my prayer is ‘Lord, let me be a blessing to someone today,’” Jenkins says. “Whether it be a patient, or a family member. Because sometimes the family members need that blessing more than the patient.”

As a charge nurse, her hand is on the pulse of the Emergency Room. She does initial assessments and is the go-to person whenever an issue arises. “When you’re really busy, particularly in the ER, you’ve got people in the hallways. You’ve got every room full— and you still have ambulances coming . . . that can be stressful,” she concedes.

Working as a team helps get them through. “That [teamwork] is one of the things I love,” she says. “No one’s scared to ask for help. That’s because generally they don’t have to ask.” Everyone just rises to the challenge.

Jenkins enjoys making a difference in people’s lives. “My love language is acts of service. I get a lot of gratification out of making a difficult situation a little less difficult by showing them empathy, compassion, and understanding,” she explains.

Her upbringing as a Christian, and her beliefs, give her the hope and strength that enable her to do her job. It entails more than physical care. She caters to the patient’s— and the family’s— emotional needs in a time of crisis. At times, that may mean acting as a chaplain. She may ask if the patient or family wants her to pray with them. “I’ve never had a patient or a family tell me no, ever,” she says.

She has a special compassion for those who can be misunderstood: Alzheimer sufferers and the mentally ill, for example. But her concern also extends to those who need help because of self-inflicted problems. “They’re human. This is the place that they are in,” she says. “You just need to love them— as they will allow you.”

Jenkins’ family migrated to the Frostproof area from Chandler, Arizona, when she was just a toddler. By the time she was a teen, she knew she wanted to become a nurse. She was raised to serve others, and medicine attracted her. “I just kind of always knew that’s what I wanted to do,” she states.

A nurse since 1999, she has worked for LWMC for eight years, six of them in the Emergency Room. She earned her Associates of Science degree in nursing from Polk Community College (now Polk State College).

One of her challenges is dealing with bad outcomes— those times the patient comes in talking and dies in less than an hour. “That’s extremely difficult,” she says. “Knowing you did everything you could have possibly done— and they still didn’t make it. Those are the sad moments,” and that’s when she knows she has to keep going. She knows that she has to keep speaking her language in order to be a blessing for the next ER patient.

Lakeland Regional Medical Center

Marjan Conklin

The most gratifying calling is to help someone in need

There is no avoiding the sting of death when you work in an Emergency Room. At times, patients die, no matter what you do. The most memorable time for Marjan Conklin, a clinical services coordinator at Lakeland Regional Medical Center (LRMC), involved a patient in respiratory distress. He came in with a “Do Not Resuscitate” order.

As his wife of 60 years watched, the emergency crew tried to make him comfortable. “She told me he was a professional pianist in his early years, so I grabbed my phone and played videos of the patient playing the piano for them,” Conklin recalls. “I sat with the patient’s wife and we cried together.”

Later, Conklin realized the memory of himself playing piano was the man’s last. “That couple will always have a place in my heart,” she shares.

Coping with loss, especially when it is not anticipated, is one of the most challenging aspects of working in emergency care, Conklin testifies, who expedites procedures and testing in a LRMC care pod.

In her job, she interacts with patients, doctors, and nurses. “Even though I am a clinical coordinator, I still maintain contact and rapport with our patients,” Conklin says. “Whether it is a difficult intravenous stick or a simple request for a blanket, I do my best to be there for that patient. Patients always come first.”

For 28-year-old Conklin, patient involvement is an important reason why she became a nurse. She loves being able to help patients on the physical— and emotional— level. “Nursing is such a gratifying career,” she says.

She enjoys her role as a patient advocate. “I am very passionate when it comes to helping and providing care for my patients. Caring for others has always intrigued and motivated me,” she adds.

Her interest in nursing dates back to her childhood, when she played nurse. “I also took medical elective classes throughout high school to prepare myself for nursing school,” she elaborates.

Conklin, who holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing from Polk State College, has five years of critical care/trauma experience. A native of Kuwait who has lived in Lakeland since elementary school, she began her career in LRMC’s Emergency Department, which has approximately 200,000 visits annually.

She enjoys the “unpredictability” of working in the Emergency Department. “It is such an adrenaline rush,” Conklin concludes. “You just never know what type of patient will come through those doors.”

CREDITS

stories by CHERYL ROGERS

photos by PEZZIMENTI